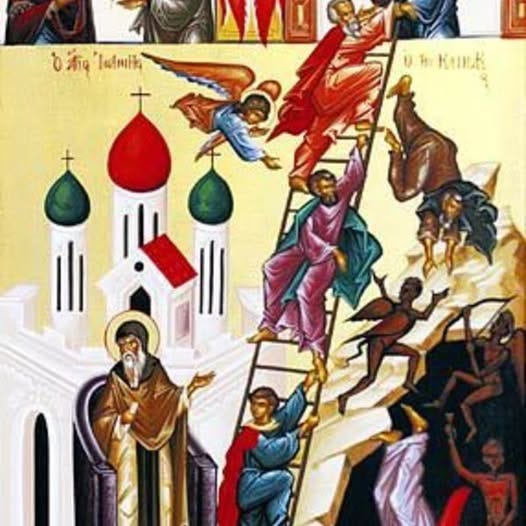

THE LADDER OF DIVINE ASCENT St. John Climacus, translated by Archimandrite Lazarus Moore (Harper & Brothers, 1959) Part 2

An Ascetic Treatise by Abba John, Abbot of the monks of Mount Sinai, sent by him to Abba John, Abbot of Raithu, at whose request it was written.

THE LADDER OF DIVINE ASCENT St. John Climacus, translated by Archimandrite Lazarus Moore (Harper & Brothers, 1959) Part 2

An Ascetic Treatise by Abba John, Abbot of the monks of Mount Sinai, sent by him to Abba John, Abbot of Raithu, at whose request it was written.

.

Step 1 On renunciation of the world. (continued)

.

11. To lag in the fight at the very outset of the struggle and thereby to furnish proof of our coming defeat is a very hateful and dangerous thing. A firm beginning will certainly be useful for us when we later grow slack. A soul that is strong at first but then relaxes is spurred on by the memory of its former zeal. And in this way new wings are often obtained.

.

12. When the soul betrays itself and loses the blessed and longed for fervour, let it carefully investigate the reason for losing this. And let it arm itself with all its longing and zeal against whatever has caused this. For the former fervour can return only through the same door through which it was lost.

.

13. The man who renounces the world from fear is like burning incense, that begins with fragrance but ends in smoke. He who leaves the world through hope of reward is like a millstone, that always moves in the same way. But he who withdraws from the world out of love for God has obtained fire at the very outset; and, like fire set to fuel, it soon kindles a larger fire.

.

14. Some build bricks upon stones. Others set pillars on the bare ground. And there are some who go a short distance and, having got their muscles and joints warm, go faster. Whoever can understand, let him understand this allegorical word.

.

15. Let us eagerly run our course as men called by our God and King, lest, since our time is short, we be found in the day of our death without fruit and perish of hunger. Let us please the Lord as soldiers please their king; because we are required to give an exact account of our service after the campaign. Let us fear the Lord not less than we fear beasts. For I have seen men who were going to steal and were not afraid of God, but, hearing the barking of dogs, they at once turned back; and what the fear of God could not achieve was done by the fear of animals. Let us love God at least as much as we respect our friends. For I have often seen people who had offended God and were not in the least perturbed about it. And I have seen how those same people provoked their friends in some trifling matter and then employed every artifice, every device, every sacrifice, every apology, both personally and through friends and relatives, not sparing gifts, in order to regain their former love.

.

16. In the very beginning of our renunciation, it is certainly with labour and grief that we practice the virtues. But when we have made progress in them, we no longer feel sorrow, or we feel little sorrow. But as soon as our mortal mind is consumed, and mastered by our alacrity, we practise them with all joy and eagerness, with love and with divine fire.

.

17. Those who at once from the very outset follow the virtues and fulfil the commandments with joy and alacrity certainly deserve praise. And in the same way those who spend a long time in asceticism and still find it a weariness to obey the commandments, if they obey them at all, certainly deserve pity.

.

18. Let us not even abhor or condemn the renunciation due merely to circumstances. I have seen men who had fled into exile meet the emperor by accident when he was on tour, and then join his company, enter his palace, and dine with him. I have seen seed casually fall on the earth and bear plenty of thriving fruit. And I have seen the opposite, too. I have also seen a person come to a hospital with some other motive, but the courtesy and kindness of the physician overcame him, and on being treated with an astringent, he got rid of the darkness that lay on his eyes. Thus for some the unintentional was stronger and more sure than what was intentional in others.

.

19. Let no one, by appealing to the weight and multitude of his sins, say that he is unworthy of the monastic vow, and for love of pleasure disparage himself, excusing himself with excuses in his sins. Where there is much corruption, considerable treatment is needed to draw out all the impurity. The healthy do not go to a hospital.

.

20. If an earthly king were to call us and request us to serve in his presence, we should not delay for other orders, we should not make excuses, but we should leave everything and eagerly go to him. Let us then be on the alert, lest when the King of kings and Lord of lords and God of gods calls us to this heavenly office, we cry off out of sloth and cowardice and find ourselves without excuse at the Last Judgment. It is possible to walk, even when tied with the fetters of worldly affairs and iron cares, but only with difficulty. For even those who have iron chains on their feet can often walk; but they are continually stumbling and getting hurt. An unmarried man, who is only tied to the world by business affairs, is like one who has fetters on his hands; and therefore when he wishes to enter the monastic life he has nothing to hinder him. But the married man is like one who is bound hand and foot. (So when he wants to run he cannot.)